By Chi Varnado | Published Thursday, Oct. 11, 2007

Republished from the original article on SDReader.com

On October 25, 2003, I go outside to touch base with the night sky and feel the air before retiring to bed. Tonight feels different. A Santa Ana is brewing and I smell smoke.

On October 25, 2003, I go outside to touch base with the night sky and feel the air before retiring to bed. Tonight feels different. A Santa Ana is brewing and I smell smoke.

I come back inside through the creaky kitchen door, releasing the knob too soon, and the glass pane rattles as if it will break. My husband Kent says a neighbor called. They smell smoke.

“Yeah, I do too,” I say, “and there are hot and cold pockets in the air outside, which means the east wind is on its way.” Kent grew up on the East Coast and is not as familiar with the natural omens of our area. Our 1920s two-story cabin is nestled in an oak-studded box canyon, located about a mile due north of San Vicente Lake. There’s only one way out of this valley that cradles five houses belonging to the four generations of our family that have lived here: three dwellings at the end of the canyon (Mom’s house, my sister’s vacant dome, and my old trailer with an add-on), my grandmother’s cabin (a quarter-mile out the road), and our own paradise across the creek.

There’s only one way out of the valley.

At 3:00 a.m. a ridge-sitting neighbor calls.

“Chi? Do you know about the fire? It’s going to get us…. You may be all right, but we’re up on top. We’re going to get it. This is it.”

I hear her words and feel the need to go to where there’s a decent vantage point on this fire. Though I turn on an old flashlight, I can barely see the ground in front of me. After fumbling with the car’s resistant door handle, I drive out our dirt road and up a neighboring ridge. I park on an overlook and get out of the car. By now the warm wind has begun to carry the daunting smell of a forest fire. I lean against the car and watch the fire-brightened sky in the distance. The first flames burn over the far ridge, and the hairs on the back of my neck rise. A bright orange snake slithers along the mountainscape as it heads toward San Vicente Lake. I’d better go hook up the rig and load our livestock before my car gets blocked in on top of this mountain.

I find Kent still in bed and convince him to get up and moving. I’m amazed at the calm in my voice. “Could you hurry and hook up the patio hose to the roof sprinkler? I’ll turn on the yard sprinklers and — oh crap…” The flashlights are dead, so I put new batteries in them. I call my sister. “We’re starting to evacuate. Did you know there’s a fire?” She doesn’t know. I call her again about moving her old horse from up the canyon.

Kent holds a flashlight and guides me as I back the truck to the horse trailer. We crank the trailer tongue down over the ball. I fumble with the emergency brake wire, weaving it through a clip dangling from under the truck, then cram the electrical plug into the receiver. We run up to the barn, yank open the door. I stand there dumbfounded for a few seconds, trying to figure out what tack to take. A wave of déjà vu crashes over me. I wonder if this will be a dry run, the way all our other evacuations have been. I shove a saddle and a couple of bridles into Kent’s arms and scoop up another two saddles to load into the back of my old Toyota wagon. We carry more armloads out and throw them into the car, until there’s no more room except for two laundry baskets full of photo albums I snagged on my way out of the house. We’ll hold off loading horses until daylight, if possible, to avoid trailering problems.

I check on the roof sprinkler, only to find that it needs manual assistance to get it to oscillate. After removing the screen from an upstairs window, I climb out onto the roof. I stand on tiptoes, slipping on the loose, mossy cedar shingles, and reach up to turn the head a few times. I get soaked in the process. Finally, the dang thing decides to work on its own. I climb back in through the window.

Kent, our ten-year-old son Chance, and I hurry out to catch the horses as it begins to get light. My sister drives past to get her old horse. My teenage daughter Kali goes off to help her. We lead our nervously snorting horses down to the rig and stroke their necks, saying, “It’s okay now.” I load the two horses first, because I know the donkey will be trickier. We tug, heave, even try lifting her feet into the trailer — all standard donkey-loading procedures — to no avail. By this time the smoke is billowing over the mountains, and I cry, “Bailey, you either need to get in now or you’re gonna have to stay here!” Fortunately, she decides to be a smartass, and within a minute she’s in the trailer and we close the door.

“Can we hurry up and go? It looks like the fire is coming!” Chance’s quivering voice conveys more than his words.

We pull out of there, leaving Kent to load the goats and dogs. We are taking the horses ten miles across town to my sister’s house.

About a half mile down the road, a woman is waving her arms for me to stop.

“Do you have room for my horse?” she asks.

“No, I’m sorry. I’m full.”

“What do I do?”

“You wait until you absolutely have to leave, then turn him loose.”

An hour later, Kali and I are on our way back to the cottage. Flames leap down the canyon walls. The smoke is thick and black. The truck barrels in the dirt road. As I turn the rig around, Kali jumps out and disappears through the smoke to rescue my uncle’s cat from the garage behind Grandmother’s house.

I yell, “Just open the door and come right back!”

“No, I’m going to get her!”

Out of the truck now myself, I run up toward the field. I see unfamiliar faces, one in a gas mask, helping Kent load goats into the camper. The strangers yell, “We gotta get out of here. Now!” I scramble to open the chicken pen and the goat gate, because the two younger non-milk goats are too scared to let us catch them, and they have to be able to get free.

Meanwhile, Kali is crawling along the floor in the smoke-filled garage, trying to find the cat. I’m worried, but I have to drive the empty rig out, since it’s blocking the road. I tell Kent, “Don’t leave without her!” A neighbor jumps into my truck. In the cloud of dust behind us, I see Kali. She’s trembling, clutching the cat in her arms.

I drop off my passenger in a neighbor’s yard. I am relieved to see the camper following behind. Kent had already brought out Kali’s truck, and his van, crammed with four of our dogs. There should’ve been five, but in the commotion no one has noticed. Kali lifts the cat into her truck and drives to my sister’s house.

We now begin our relay race out with only two drivers for three vehicles. We manage — Kent’s a runner. We both gag and cough from the smoke burning our throats. As we leave our canyon, flames, shooting a hundred feet high, blaze down the mountainside toward the Fernbrook houses.

When I was a kid, this old two-story cabin, down the dirt road from where we then lived, enraptured me. An artist had built the cottage during the 1920s, nestling it into the hillside, and the place oozed charm. No two rooms were constructed on the same level. Rockwork in the patio led the way to a cistern on top of a boulder behind the house. If I was having a particularly tough day, I would venture down here with my dog and guitar and enjoy the peaceful setting. At that time, no one lived full-time in the cabin. It belonged to several families who retreated there a few times a year. Huge live oaks shaded the house and front yard.

In 1992, Kent and I bought our paradise and moved out of my old trailer/house that I’d built on Mom’s property. It’s funny how things come around. I’d always felt the cottage was my house, and now it was. It became a kind of heaven when my better half fell in love with it too.

Unfortunately, the place had changed hands over a couple of decades. Subsequent renters trashed it. To say there was a lot of work to do on this fixer-upper would be a gross understatement; a “Condemned Notice” was posted on the kitchen door. The toilet had been ripped out of the bathroom, leaving a gaping hole in the floor. The concrete bathtub was unsightly and cooled water and buns much too quickly. I scoured the tub with muriatic acid and painted it navy blue with epoxy paint. Daylight could be seen through the cracks in the walls, so we added plywood, then painted the room antique white with blue trim.

The house sat precariously on a thin rock-and-mortar stem wall — classic Craftsman style. The back patio sloped into the living room through the rotting French doors. The Douglas fir floor was decayed and sagging. We beefed up the living-room floor with foundation supports. We dug ditches and laid pipe. We painted until our arms ached and we made innumerable trips to the dump. Anyone else would have torn the place down. But even if we’d had more money, we still would have worked with what was here. Simplicity and making do with less has always fit us.

Former owners had painted over old cowboy paintings on the dining room walls, which I knew about from childhood escapades. A friend and I applied a special solvent and removed one layer of paint at a time. We tipped the can of solution onto wadded-up rags and rubbed the edges of the pictures, working our way inward. Through several layers of paint, we uncovered cowboys flying off bucking broncos onto cactus plants. These paintings were not extraordinary, but they were rugged, free-form illustrations that had become part of the house. They belonged here. It is said that San Diego landscape painters would come up the mountain to paint this house.

An arm from the Paradise fire has started to reach around us from the north. For days we’ve been on alert to the possibility of evacuating from my sister’s place. There are four fires burning now, eating up vegetation and dwellings. Authorities fear that the fires might connect and overwhelm the entire county. We sleep hesitantly, looking out the camper window at the glowing horizon. The kids stay in the house, while Kent and I lie on our bed in the camper, over the truck cab. We can see out to the mountains toward our place. “I wonder if this is what a volcano looks like,” I say.

Two days after evacuating, Kent and I decide to go home without the kids. We park the van at the top of Mussey Grade, because the police won’t let us drive down. Flames are still burning the brush behind the homes at the top of the grade. The smoke chokes us. We each carry water and a bag of nuts and hoof it down the road.

We make our way into the canyon. Trees and bushes are still burning all around us, but at a slower rate, as the bulk of the fuel is gone. The first house we pass, an old rock dwelling called the Fernbrook House, stands within its smoking surroundings. Up the hill and off to the left is a new house that seems to have escaped the fire, but several neighbors have lost their homes.

Nobody is here. It feels as if we’re moving through a war zone. The tractor guy’s abode has escaped obvious damage, but his outbuildings are smoldering. The Lady Farmers’ house is flattened, and there’s no trace of the barn. Melted aluminum has oozed out from the old cars parked for decades in the canyon, like trails of metallic blood on the ground.

Once we reach our property, Kent heads to the field, while I make my way to the house. I can’t see it yet, because I haven’t passed the boulder by the driveway that shields the view. My breathing is shaky and labored. I take another few steps, stop, and gasp. Our rock chimney towers above the smoking debris of the absent house. Rock steps lead up to the site of our cherished home, now in ruins. My heart sinks. Everything we have worked so hard at creating and protecting is gone, burned beyond recognition. The refrigerator, washing machine, piano, beds…all gone. Water dribbles out of the melted stand pipes. The stench nauseates me. I have loved this house since I was a girl, and now it feels as if a part of my soul is gone. My eyes well with tears, but I turn them off. It’s the only way to endure the huge task that lies ahead. I pick up a blackened pair of cutters to shut off the water meter. Without speaking, Kent approaches. The enormity of it all seems to affect him as it has me. We stand together and stare. My eyes fill again.

I trudge off to the field, where every barn and outbuilding is gone, except one, the outhouse. What a surprise — it even sits under a crisped tree. I go in and relieve myself, feeling fortunate that the structure remains, remembering how Dad built it for us.

I walk back to join Kent. A few oaks in our front yard look okay, but the rest of the canyon is devastated, a wasteland, a lunar landscape.

A few days later, the ashes are still hot, but the kids have managed to pull a few burned items from the debris. I pick up a piece of something that must have been part of the piano. It dissolves in my hand.

Kali and Jessie, my oldest daughter, who stayed in San Diego during the fire, rummage in the remains that have fallen from their upstairs bedroom to join the artifacts in the dining room. The birdcage, a twisted mass of metal, leans against a warped antique bed frame.

Later, Chance points into the ashes and says, “Is that what I think it is?”

I reply carefully, “I think so, Chance…. You sure have eagle eyes.”

Down in the ash are the bones and burned tufts of hair of Patch, our old, blind dog. The one that Kent forgot to save. Kent is up on the hill at that very moment, calling for Patch. Chance and I exchange an uncomfortable glance. Neither of us will mention our findings to Kent that day, since he blames himself so harshly.

In the morning I tell Kent that Chance had found Patch and that he seemed spooked.

Kent says, “Last night, when I was helping Chance with his bath, he asked if you had told me anything. I wondered what he meant.”

Later, we talk about Patch with the kids. None of them wants to go back to the cottage with us. We respect their wishes. Kent and I bury Patch’s remains in the orchard. Kent says, “It’s okay that the kids aren’t here. Doing this together feels right, somehow.” I say, “I think so too.” We walk back down the hill holding hands.

Two weeks later, trees are still burning, and a fire marshal drives up to check the area. He takes in the devastation at this end of the canyon. Eyeballing what’s left of Mom’s wood-burning stove, he says, “Looks like this area saw the worst of the Cedar Fire. It took between 2000 and 3000 degrees Fahrenheit to melt that cast iron.”

Our extended family has lost five houses in this canyon. Family history and treasures have gone up in smoke. Still, we paw through the ashes.

Chance finds a few burned coins from the area where his room used to be. We’re all in different spots, picking up items that seem to call to our fingertips. The flattened house feels much smaller now, demarcated only by the crumbling edges of the foundation.

Kali finds some pinkish-colored ashes amidst pieces of the clay cookie jar that contained my mother’s ashes. We’d lost Mom to a brain tumor seven months earlier. Kali looks subdued, raking her fingers around her feet.

“How could you forget Gramaset, Mom?”

“I don’t know. We barely got ourselves and the animals out.”

My sister says, “She was already ashes. She belonged here.”

“But now she’ll just go to the dump,” Kali complains.

“Pick up those different-colored ashes and put them in this vase,” I say, pulling up an oriental pot that had been on my dresser.

Kali takes the vase and begins her task. I dig again through the area that had been our dining room, where the china cabinet from my grandma in Mississippi once stood. I feel something hard and smooth through my gloved fingers. I grasp the familiar form, pulling it toward me through the ash. I look at it disbelievingly before holding it up to show everyone.

“Can you believe it?” I shriek through the mask. “It’s in perfect shape!”

My family stares with widened eyes — they too recognize the clay torso of a woman, a sculpture Mom made for Dad when we were kids. She’d made it with red mud from the clay pit on the mountain. This was the piece she used to cast her bronze replicas at the foundry at Palomar College.

This ceramic bust, beautifully proportioned, is one of my favorite works of art. This is the angel in the rubble. Dad gave it to me after Mom passed.

The compassionate side of humanity emerges in the aftermath of the Cedar Fire. Friends, relatives, and volunteers generously donate their time to help us clean up. This is an outrageously dirty and never-ending task. We haul wheelbarrow loads of twisted metal and the charcoaled remains of our former lives into 40-yard Dumpsters that the county provides. Two women cook lavish dinners that each feed us for almost a week. Others give us money hidden in sympathy cards or at the bottom of boxes filled with donated clothes.

In another week the Disaster Emergency Center is up and running. They take over the old post office building on the far side of town. Kent and I wait in line on that first morning and get our FEMA number. Each department needs its own questionnaires and forms filled out. It’s frustrating to fathom the amount of paperwork and phone calls it takes to start your whole life over again.

About a month after the fire, we’re finally able to get a small portion of our piddly insurance money, enough to buy two small, used trailers to live in. It’s time to move out of my sister’s yard. We still have no electrical power, so we purchase a generator from Home Depot and learn to use it. The noise it makes is deafening. We try to run it only a couple of hours in the morning and evening, just enough to charge the battery.

Kent and I consider our options for building, weighing cost, the desire to blend into the environment, as well as questioning what we can live with. I know that at this point I need a house I will love, or someday I may not want to come home. After losing Mom and my house in the same year, I feel fragile.

I’ve always loved log cabins, and after a bit of research and soul-searching, we find a company that builds with big, dead-standing lodge-pole pine. It’s important to us that it be handcrafted, not machine-milled. This outfit agrees to come spend the summer camping out in our yard and eating my trailer cooking in order to erect our structure properly. This alternative style of building is not common knowledge among contractors in Southern California.

In April, I submit our plans to the county building department. I call them after the estimated “ten days max for fire victims to get their plans approved.”

“No, they’re not ready yet,” the phone attendant states.

Three weeks later, I plead, “I need to get these plans through right away. The contractor willing to do my foundation is running out of time to budget for me. We need a house! I lost my mom seven months before the fire, and then we lost everything. I have a teenage daughter I’m really worried about, as she was very close to her grandmother. Our family is living in two tiny trailers, and it’s pulling us apart. I really need your help!” The building department duly expresses condolences, then continues with 12 pages of corrections. I wonder if they know how volatile a 16-year-old girl can be when she’s so recently lost her favorite person in the world (Gramaset) and then every tangible item she could call her own. Her displaced anger toward me is slashing away at my self-esteem.

Six weeks later, I present the engineer with the plan-change artillery loaded in my backpack: Wite-Out, pens, tape, glue stick, pencil, and eraser. I am a woman on a mission, and I won’t take “no” for an answer. This time it works.

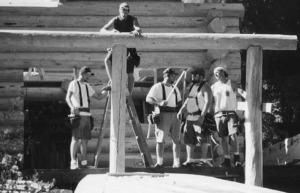

July 2004, nine months after the fire, brings both excruciating heat and our log delivery. The foundation and subfloor are ready. The 35-ton crane sets up in our front yard and begins its spiderlike dance. The boom is shortened, and the massive metal mandibles lower down to the tractor trailer, loaded with 2000-pound Tootsie Rolls. Our log crew’s work rhythm synchronizes. Amos guides the hook to the log and clamps it in the center, where it can be lifted a few inches to determine whether it’s balanced. Merl lends his hands to the teeter-totter, and the process is repeated until the load is centered and tied on. Amos gives the crane operator a thumbs-up, and the dangling stick rises slowly over the oak trees, 50, 60, 80 feet up, where it looks like a toothpick in the sky. It trapezes toward the south mountain before descending to our future cabin. Adam and Justin stand on top of two perpendicular walls, clad in shorts and sandals, arms reaching upward to each end of the incoming log to steer it into its resting place. Bruce is on the ground, giving the crane operator hand signals, not unlike sign language for the deaf. It might as well be, for nothing can be heard over the generator and crane.

By October, I’m spending most every day and evening staining the inside trim. All the nail holes need to be filled with wood putty, sanded, and then two clear coats have to be hand-brushed over it.

One evening, Kent finds me still at it when he gets home from work.

“How much longer are you going to be here?” he asks.

“Oh, I don’t know,” I respond tiredly. “At least a couple more hours.” I point out what I want to accomplish tonight.

I continue painting. Later on, sometime after 9:00 p.m., I hear the door open and smell a wonderful hunger-enticing aroma. Kent appears with plates of baked salmon and salad, along with a bottle of wine. He says that Chance has already gone to bed. We sit on upside-down buckets with the plates in our laps and enjoy one of the most delicious meals I’ve ever had.

“You know, all this wood is sure interesting to look at,” says Kent. “I don’t think we’ll ever get tired of it.”

“Yeah, see this knot here,” I point out. “It’ll be right over the dining-room table. No telling what our friends will see in it when they sit here drinking wine with us.”

The dining room inside the cabin, ready for entertaining friends, sipping wine and reflecting upon the journey so far.

Indeed, our comrades have seen a variety of images in this gnarly indentation of the log: an old woman with a long nose, a ship traversing a tumultuous sea, and a prairie dog coming out of its hole. The knots are too numerous to count. They will entertain us for the rest of our lives.

Current Day image of the Cabin. Chi And Kent are currently sharing the joy and beauty of their home and property. To learn more visit Facebook.com/gnomewoodcanyon or Airbnb.com